Life and Legacy of Lennie Tristano

Jazz History Paper about Lennie Tristano, written for my undergraduate studies in Jazz Piano @ The University of Northern Colorado. Jazz History Course taught by the great jazz Historian Professor Brian Casey

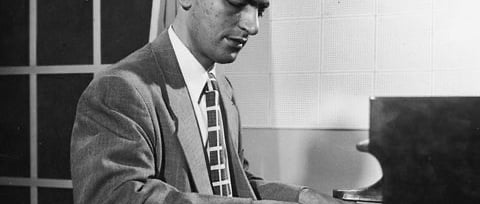

Lennie Tristano, born Leonard Joseph Tristano (March 19, 1919 - November 18th, 1978) was an innovative jazz pianist, arranger, composer, and pedagogue. Born in Chicago, Illinois to an Italian-American mother and Italian father, Tristano showed an early interest in the piano, sitting at his family's piano at the age of three, and beginning classical piano lessons at the age of eight. He showed early signs of musical aptitude, working out simple songs on the player piano around the age of four. For several different reasons, ranging from his mother’s pregnancy taking place during the flu pandemic of 1918-19 to his bout with measles at age six, he completely lost his eyesight before reaching the age of 10. While this presented many challenges for Tristano, his love for music persisted. He regularly learned and tried different instruments during his formative years through middle school and high school, from saxophone to clarinet to drums. He had his first gig at the young age of eleven, performing clarinet in Illinois brothels.

Throughout high school, Tristano learned and performed many difficult classical piano pieces, ranging from Bach and Beethoven to Chopin and Liszt. Tristano and his friends would also listen to jazz greats, such as Louis Armstrong, Roy Eldridge, Earl Hines, and Lester Young (with whom he would eventually play). In addition to this, Tristano would regularly frequent music clubs in Chicago from the age of 15, where he was typically the only white attendee. It was here that he would listen to music and learn about African American culture. He went on to attend the American Conservatory of Music in Chicago, graduating with a bachelor's degree in music performance in 1941. He stayed for a few more years to pursue graduate studies but never obtained a master's degree. Throughout his college years, Tristano continued to show natural musical aptitude and drive, despite his blindness. He noted in an interview “I took two-year harmony courses in six weeks. Counterpoint-it was so easy. Until I was in my middle twenties, I never worked hard at anything.”

In the mid-1940s, Tristano began playing piano and saxophone in various bands around Chicago, making a name for himself on the jazz scene. He also began to teach privately, most famously teaching the saxophonist Lee Konitz, who would later become a collaborator and dear friend of Tristano's. Tristano’s growing love for jazz, along with many other factors, inspired him to move to New York City in the spring of 1946. He played at various venues, started to record, and was continuing to make a name for himself. It was in 1947 that he met Charlie Parker, playing with him and other bebop legends like Dizzy Gillespie and Max Roach. He recorded with Parker in 1951.

Aside from playing in clubs with greats like Charlie Parker, Tristano established his own group in the late 1940s with whom he would record his first albums, ranging from drumless trio to sextet. The group for one of his most famous albums, Crosscurrents, recorded in 1949, included Lee Konitz on alto sax, Warne Marsh on tenor, Billy Bauer on guitar, Arnold Fishkin on bass, and Denzil Best on drums. Tristano was way ahead of his time. Two tracks on this album, “Intuition” and “Digression” were the first instances of free jazz ever recorded and would posthumously induct Tristano into the Grammy Hall Of Fame in 2013.

In the early 1950s, Tristano would record and perform with his aforementioned sextet, but they struggled to find work and would eventually break up. In 1951, Tristano created his own label, called “Jazz Records,” setting up a studio in his Manhattan loft. That same year, under his new label, with bassist Robert Ind and drummer Roy Haynes, he recorded the very first overdubbed jazz records, making jazz history, by superimposing one piano track over another. The results were the tracks “Passtime” and “JuJu” from the album Descent into the Maelstrom.

Tristano would go on to have a busy and successful recording career throughout the 1950s and 1960s, recording 14 more albums as a leader. In addition to working in NYC and throughout the states, in the mid-1960s, he toured Canada and Europe as a solo pianist. Tristano’s last public performance took place in 1968. After that, he declined various offers to perform and focused on teaching. On November 18th, 1978, at only 59 years old, “Tristano died of a heart attack… The death certificate… indicates that the immediate cause was chronic bronchitis with emphysema.”

Tristano had a unique approach to music. His philosophy surrounding music and improvisation was unlike most musicians. Writer for Metronome Barry Ulanov noted that Tristano “was not content merely to feel something, ... he had to explore ideas, to experience them, to think them through carefully, thoroughly, logically until he could fully grasp them and then hold on to them.” Tristano was also very critical of the free jazz movement of the 1960s. He saw the music as a way to express negative emotion, which he disapproved of, and also saw the music as random and chaotic. Art Blakey, an innovator in the hard-bop idiom, agreed with Tristano and noted Tristano’s earlier free jazz recordings. He stated ”The thing some of those freedom musicians are trying to do I heard Lennie Tristano do that sort of thing years ago, but it had a direction. It made more sense to me than what they're doing now with just everybody going. That's one of the easiest cop-outs.”

Tristano’s playing style was also unique. Influenced by the likes of Art Tatum, Lester Young, Bud Powell, and others, Tristano had technical mastery and a deep understanding of the bebop language. However, what made his approach unique was what he played, how he wanted his rhythm section to play, and how he approached improvisation. Unlike most bebop players, he preferred a steady and even rhythm section to paint long strings of angular, swinging, and harmonically sophisticated lines in his right hand, with a minimalistic approach to left-hand comping, making use of non-traditional voicings in low ranges. Using his tremendous technique, he would implement double-time feels, triplet lines, and weave seamlessly in and out of chord changes. His style is exemplified in his recording of “Line Up,” from his 1955 self-titled album Lennie Tristano.

Tristano also has a particularly underappreciated and unique legacy as a teacher, utilizing many non-traditional and innovative techniques in his pedagogical approach. Unlike the somewhat “cookie-cutter” approach to jazz education in college-based programs today, which emphasizes chord-scale theory, arranging, and intellectual exercises, Tristano believed the acquisition of improvisational ability to be mostly aural. He also believed in the importance of dedication and commitment to learning, requiring his students commit to a minimum of one year of lessons. He utilized techniques that he felt led to pure and spontaneous improvisation, where the improviser could truly express what they were feeling in the moment, and have the freedom to express themselves melodically, harmonically, and rhythmically. One such technique that Tristano taught to his students was the importance of practicing away from one’s instrument and practicing using intense and careful visualization. Once his students could visualize and sing, in their mind, all of the different possible intervals on their instrument, he would have his students practice scales, exercises, techniques, and solos away from their instrument, requiring that they actively imagine both the instrument and all of the correct pitches in their mind’s eye. Many of his students have noted just how incredibly effective this technique was for the development of their playing.

Interestingly, recent research in brain plasticity has proven the effectiveness of Tristano’s method. Tristano, being the genius he was, understood this many decades earlier. His approach to jazz pedagogy also involved a novel approach to transcribing solos. In her Ph.D. thesis, entitled “Jedi mind tricks: Lennie Tristano and techniques for imaginative musical practice”

Marian Jago, a student of Lee Konitz, describes this process. “The student was not simply to copy pitches, but to learn to sing along in such a way that they could visualize themselves play- ing the solo. Time feel, accent placement, timbre, articulation, and mood were all as essential as the pitch elements of the solo and needed to be embodied in the process of this initial learning of the solo.” When a student had mastered all of this and could embody the solo in their mind’s eye, they would then play the solo on their instrument. Due to the effectiveness of Lennie’s approach, the process of actually learning to play the solo was almost spontaneous, and would effortlessly integrate into the students playing. Along with these aural techniques, Tristano had many other imaginative and creative ways to learn not only how to improvise authentically but to master music as a language, to be able to produce vocabulary spontaneously, as if speaking your native tongue.

Tristano’s legacy and contribution to jazz, to this day, goes largely unrecognized. However, it is felt even by those unaware of his contributions. He influenced many great jazz pianists, such as Dave Brubeck, and most notably Bill Evans. In this sense, the link between Tristano and all of the modern great jazz pianists, and soloists in general, becomes easy to recognize. In addition, Tristano’s legacy continued into the work of his most famous student, Lee Konitz. Konitz had a powerful command over his instrument and maintained a unique style throughout his entire career. Very few instrumentalists are able to develop such a personal and unique approach, and while this is a testament to Konitz, it is also a testament to the pedagogical genius of Tristano. Konitz went on to influence many other great jazz saxophonists we recognize today, like Art Pepper and Paul Desmond. From his early days on the player piano to his high-school days playing Chopin, from his jam sessions and gigs with Bird to his innovative recordings, and from his final performances in the 1960s to his private teaching until his death, Lennie Tristano is truly one of the greatest improvisers, innovators, and educators in jazz history.

Bibliography

Ind, Peter. Jazz Visions: Reflections on Lennie Tristano and His Legacy. London: Equinox, 2007.

Jago, Marian S. “Jedi Mind Tricks: Lennie Tristano and Techniques for Imaginative Musical Practice.” Jazz Research Journal 7, no. 2 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1558/jazz.v7i2.20971.

Ulanov, Berry, “Master in the Making” Metronome, Vol. 65 no. 8 (August 1949), 14

Shim, Eunmi. Lennie Tristano: His Life in Music. University of Michigan Press, 2007.